Maauro’s Gender- Why Female?

On Gender

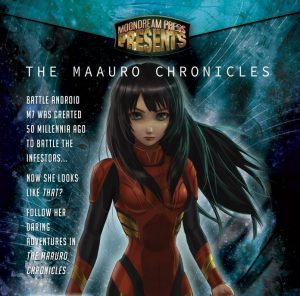

A writer friend of mine turned to me after reading My Outcast State and said. “You know it would never have occurred to me to make the robot female.” I was surprised and said that it would never have occurred to me not to. The dynamics of human nature are much more complicated between male and female in my opinion than in the same gender. Not better, or worse, just more complicated. But that also begged the central question. Why did the Maauro have a gender? I could have gone with male, and figured that I wouldn’t need to write as much dialogue as shipboard conversations might be limited to grunts and curses. Or I could have gone the way of the Professor Jameson stories where sex roles were left behind with biological bodies.

Maauro makes a conscious choice to become female when she looks for a place for herself in the new age and new civilization that she is “reborn” into. This choice is made quickly, but not without thought. Something in Maauro, some basic animus, either is or is drawn to the female. So she adopts, though not perfectly, a female guise. Hint, there is an anime look to Maauro that is also deliberate.

From the first moments after she adopts her new appearance, it has a definite effect on Wrik Trigardt, the first person of this new time that she meets. Laws of attraction are unwritten, unreliable but immutable. We are calmed by beauty, by attraction and Wrik, who is originally Maauro’s prisoner, is made more tractable by her less frightening appearance. For Maauro this creates something of a feedback loop. The more she “acts like a girl” the more complicated and enriching are her interactions with others, most particularly Wrik. She very deliberately experiments with this new found ability, sometimes to the point of manipulation (but always for his own good.)

One of the things that I have heard from female readers is how much they enjoy Maauro’s journey of discovery in regard to her gender. Though she can punch through steel plate, there is something about the small rituals of being female that appeal to her. She also finds the life, or the emotionality that she is embarking on, strange, unfamiliar and sometimes frightening. Women readers have told me that they have seen aspects of their teen years and the challenges they faced in exploring their own choices and decisions, mirrored in Maauro’s quest. In some respects the fact that she has existed 50,000 years (virtually all of it in isolation) and that she was made and not born, do not make her experience of “growing up” that different.